The Pitchfork Ranch

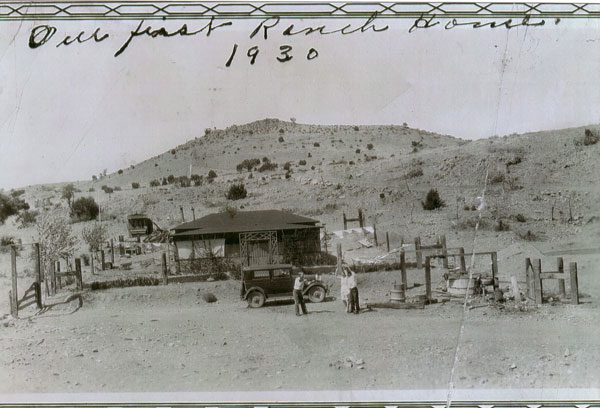

The original headquarters built in 1923. Notice the young cottonwood tree on the lower left and the holdup near the car.

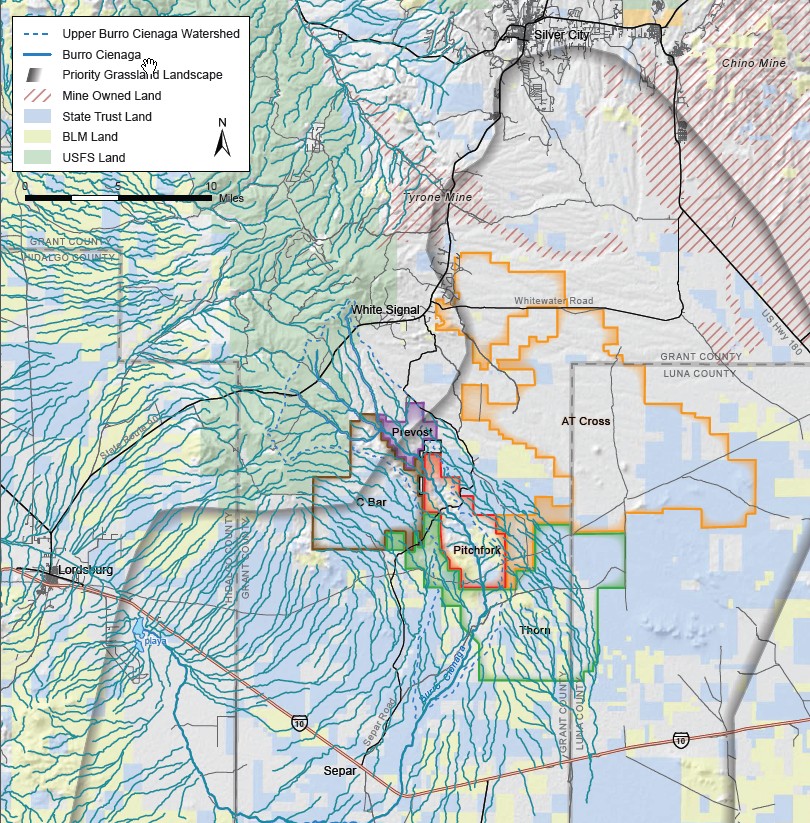

The Ranch lies at 5100’ elevation, just west of the Continental Divide in southwest New Mexico. Although mountainous, the land is primarily rolling Chihuahuan grassland, one of the most biologically diverse arid regions in the world. A one-hour drive south of Silver City, the Pitchfork is six miles from the nearest neighboring ranch and consists of slightly more than 11,000 checker-boarded, split-estate acres (we own the surface, the government or someone else owns the subsurface mineral rights), 5,160 deeded, the balance state and BLM lease land, as shown on the Pitchfork Area Map below.

The dominant landmark is Soldier's Farewell Hill (6173’) near the historic Butterfield Trail and way station #19. In the late 1880s, this land was part of the historic “Diamond A Ranch” or “Gray Ranch” in the New Mexico Bootheel. Later known as the "McDonald Brothers" or "Bart McDonald place," these lands have been in cattle production for well over a century. In the late 1890s a Civil War veteran gave 5-year old Bartley McDonald a heifer, registered the three-pronged "pitchfork" brand for the boy and thus the ranch name and brand.

"Native grasslands are now among the world's most endangered ecosystems." "Springs ecosystems (which include ciénagas) are among the most threatened ecosystems on Earth." This ranch has both. Archaic peoples, Athabaskan, Mimbres, Apache, Spanish and finally Anglo settlers lived along the 48-mile long Burro Ciénaga, a unique desert wetland and the ranch’s most important feature. A Spanish term meaning "slow moving water or marsh," the ciénaga is perennial and bisects the ranch north to south, two miles above ground, seven miles balance subsurface, fed by perennial Ojo de Inez (now Ciénaga Spring) and canyons that drain from a 58-square-mile watershed. Extreme flood and drought cycles, eradication of beaver, presence of sheep of Spanish settlers, and corporate cattle overstocking in the late 1880s, agricultural re-contouring and the absence of fire have dramatically altered the area's natural marsh balance and deeply entrenched the ciénaga.

The northern quarter (that we are “re-wilding”) and southern three-quarters of the ranch, about 2,500 and 8,500 acres respectively, are set apart by Separ Road, a Grant County maintained dirt road that runs 30 miles from the towns of White Signal on Highway 90 to Separ on I-10. The Pitchfork — surrounded be seven ranches, with no urban encroachment — is midway between the two.

Raised in Phoenix, living in Casa Grande, Arizona, for 32 years, we bought the ranch in 2003 and retired to the property, permanently living at the ranch headquarters. The buildings were refurbished or expanded in keeping with the period of their original construction, starting in 1923 through the early 1950s.

We are following restorative management practices and natural climate solutions, planning to leave the ranch to an entity that will maintain its historic integrity, support ranching, honor the conservation easement and protect these open spaces.

The overarching goals for this ranch are habitat repair and carbon sequestration, using "flood-n-flow" based restoration practices and accompanying sediment deposition to nudge the ciénaga and surrounding land toward its pre-settlement condition — to get the water back. Ongoing installation of grade-control structures is helping the ciénaga and surrounding land reclaim itself and reconnect surface and groundwater. Goals are to: refurbish the headquarters while retaining its historic character, monitor photo points and piezometers, perform water and soil data collection and mapping, raise the ciénaga bed, sequester a portion of the legacy load of atmospheric carbon, restore traditional and uplands, improve infiltration rates, fix roads, rebuild the cattle herd, provide science, research and education opportunities, protect the archaeology, improve habitat for wildlife and imperiled plants and animals, restore low-intensity fire and prevent range land fragmentation.

Zuni Bowel grade control structure that created what has been dubbed the “No Thank You Ma Am Pond” in a riparian reach of the Burro Ciénaga below the historic ciénaga.

Burro Ciénaga at flood stage near the headquarters and outbuildings,

Video: Cinda.

Burro Ciénaga Watershed & Surrounds

Map credit: Steve Bassett, The Nature Conservancy

The 56-square Upper Burro Ciénaga Watershed is identified by blue dashes (---), with the three drainages — Whitetail Canyon, Walking X Canyon and C-Bar Canyon — converging on the northwest border of the Otto Prevost Ranch where the waterway courses 3-miles through the Prevost (fairly un-incised), 1/2 -mile on the C-Bar, (severely incised), 9-miles on the Pitchfork (similarly incised), 5-miles on the Thorn Ranch (incised) where it continues south and goes under Interstate-10 and then angles westward toward Lordsburg where it empties into a playa, making it a closed-bason of non-navigable waters, meaning we don’t need to obtain clearance from US Army Corps of Engineers for our restoration work. Importantly, the gray shading means much of the watershed is within the Priority Grassland Landscape.

What's Been Accomplished So Far

- Installed more than 1,000 grade control structures, 250 in the Burro Ciénaga and over 750 in the 33 side channels that drain into the 9-mile reach of the 48-mile long watercourse on the ranch..

- Captured many thousands of tons of sediment.

- Raised the channel bottom of the Burro Ciénaga channel two feet throughout and five feet in some locations.

- Raised the water table in the ciénaga 11 inches.

- Established more than 1,000 new trees: Gooding’s willow, Cottonwood, Coyote willow, Desert willow.

- Removed cattle from five miles of the Burro Ciénaga.

- Introduced endangered Aplomado falcon, Gila topminnow, Chiricahua leopard frog and candidate species Wright's marsh thistle.

- Removed three large cattle-watering dirt tanks and restored two.

- Discovered the Euphorbia rayturneri, a plant previously unknown to science.

- The Bureau of Land Management installed a rain-water catchment, surrounded by a fence to keep cattle out that allows water on the driest part of the ranch 365 days a year.

- We have an agreement with the Natural Resource Conservation Service for three additional tanks in 2020.

- Adopted a fire management plan for the reintroduction of fire.

- Identified 34 Mimbres sites along the ranch’s nine-mile reach of the Burro Ciénaga.

- Scientists maintain lists of species for birds, mammals, amphibians, reptiles, fish, moths, butterflies, plants & grasses.

- Published a paper for the Gila Symposium on restoration on the Pitchfork Ranch and a second paper on Ciénagas.

- Wrote a Wikipedia article: Ciénega.

- Received 14 grants for ranch restoration and introduction of endangered species.

- Installed a series of 11 piezometers, devices hung in pipe-driven monitoring wells that measure aspects of groundwater.

- Given 23 PowerPoint presentations on restoration, ciénagas and the climate and species extinction crises.

- The ranch received the 2013 American Fisheries Society, Arizona/New Mexico Chapter and the 2018 Achievement for Conservationist of the Year Award by the Seventh Natural History of the Gila Symposium.

- Brandon Bestelmeyer and staff of the USDA-ARS-Jornada Experimental Range in Las Cruces, NM completed ecological site and soil mapping of the ranch.

- Maintained same location/same day repeat photography in four directions at 11 locations for 17-years.

- The ranch has a small herd of Charolais (white coat) cattle that are grass fed and grass finished, running 15 degrees cooler than black cows, important in the Southwest because of climate change.

- Provided multiple occasions for students at the Aldo Leopold Charter School in Silver City New Mexico to learn how to install grade-control structures and education or study opportunities for several dozen classes and groups ranging from grade school to post-doc.

- Adopted a Management Plan

- We have a pending request before the Bureau of Land Management for the ranch’s federal land to be designated as an Area of Critical Environmental Concern.

The Pitchfork Ranch History [ PDF ]

Historical Artifacts on or Near the Ranch

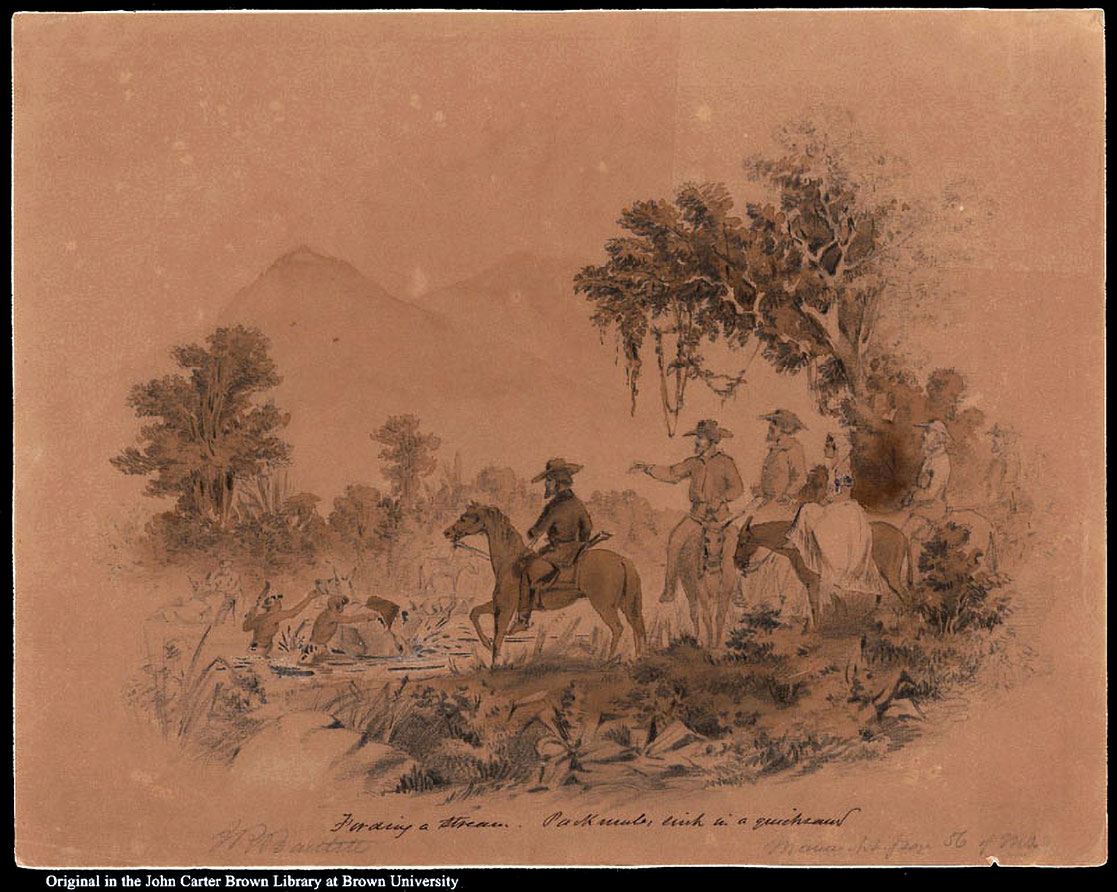

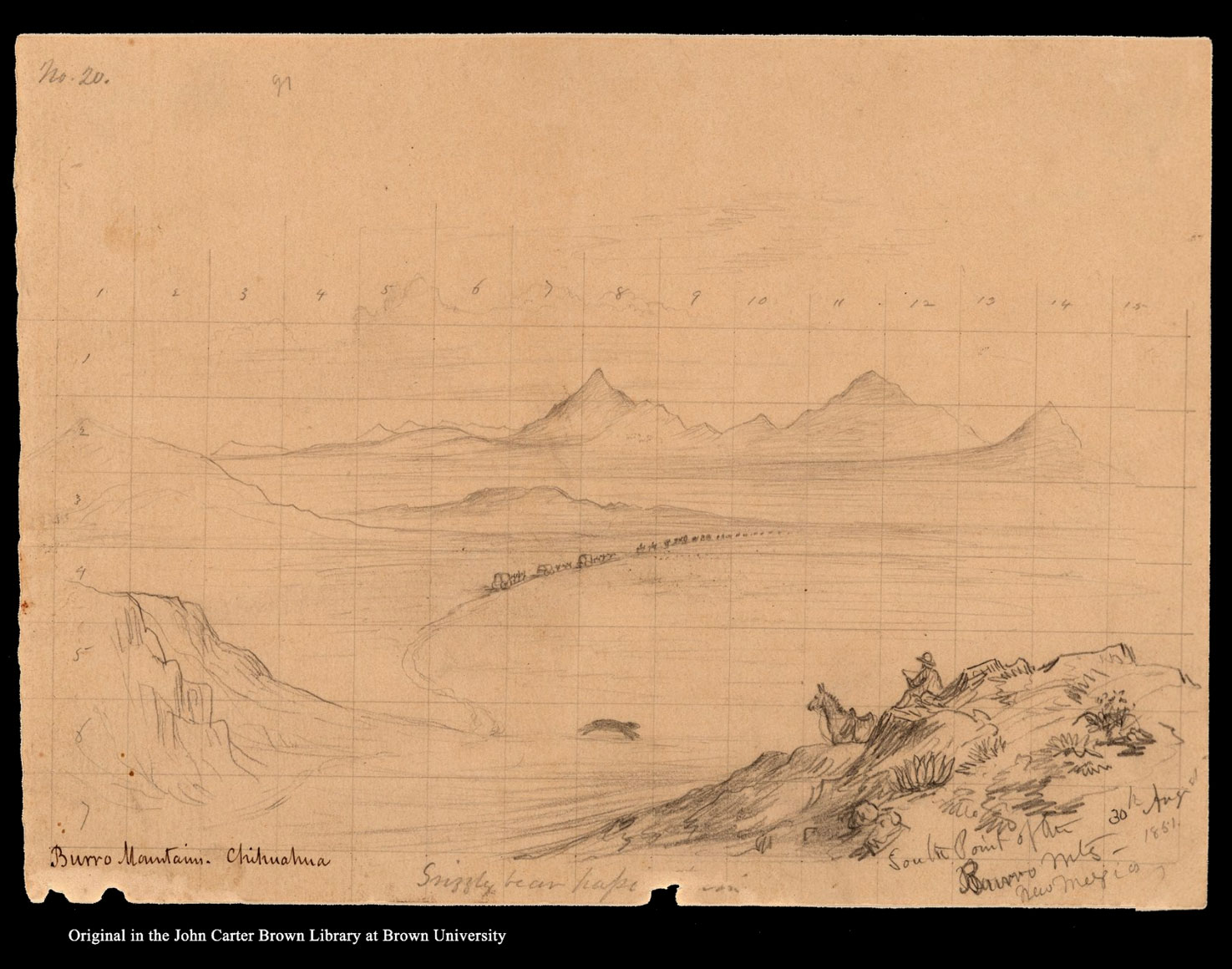

The historic Butterfield Trail goes through the Pitchfork Ranch and the remains of Soldier’s Farewell Station stage — located at Soldier’s Farewell Springs (Los Penasquitos) between Cow Springs (Ojo de la Vaca) and Steins (El Peloncillo) — stop is pictured here, located just off the ranch, named after Soldier’s Farewell Hill, an area landmark on the ranch.

The above drawing is by John Russell Bartlett. To the right is a photograph of the exact location where Bartlett portrayed himself on August 30, 1851. The United States Boundary Commission was surveying the yet established Mexico-United States boundary after the Mexican American War and passed through the land that became the McDonald and eventually Pitchfork Ranch. We were living here for less than a year when we heard a knock on our kitchen door, the first of less than a dozen since living here. It was Jerry E. Mueller, retired professor from the University in Las Cruces, New Mexico and his two grandsons. He asked for permission to look for the site on the ranch where Bartlett drew this sketch when the Commission passed through this land, headed for what would become Arizona. He found the location, returned later and I went up there with him and took this photograph of Jerry seated where Bartlett had pictured himself 155 years earlier.

The above drawing is by John Russell Bartlett. To the right is a photograph of the exact location where Bartlett portrayed himself on August 30, 1851. The United States Boundary Commission was surveying the yet established Mexico-United States boundary after the Mexican American War and passed through the land that became the McDonald and eventually Pitchfork Ranch. We were living here for less than a year when we heard a knock on our kitchen door, the first of less than a dozen since living here. It was Jerry E. Mueller, retired professor from the University in Las Cruces, New Mexico and his two grandsons. He asked for permission to look for the site on the ranch where Bartlett drew this sketch when the Commission passed through this land, headed for what would become Arizona. He found the location, returned later and I went up there with him and took this photograph of Jerry seated where Bartlett had pictured himself 155 years earlier.

This was an era before the invention of the camera, so artwork was the mainstay for such tasks. Mueller published An Annotated Guide to the Artwork of the United States Boundary Commission, 1850 – 1853, Under the Direction of John Russell Bartlett in 2000 where he reviewed many sketches by Bartlett and the artist who worked with him. Mueller also completed Bartlett’s autobiography in 2006: Autobiography of John Russell Bartlett.

When Bartlett passed through this land, he had earlier rescued Inez Gonzalez, a young Sonora, Mexican girl who had been captured by a renegade group of Pima Indians and sold to an American trader who was taking her to Santa Fe to be sold into domestic work, prostitution or whatever would return the most money. Bartlett rescued Inez and she accompanied the Commission for several months before they returned to her family in Sonora, a tale that is fictionalized by Nancy Valentine in J.R. Bartlett and the Captive Girl, 2018. When the Commission passed through here, Bartlett renamed a spring on the ranch in her honor, Ojo de Inez. Bartlett recounts these events in his two volume Personal Narrative of Explorations and Incidents in Texas, New Mexico, California, Sonora and Chihuahua, 1850 – 1853, 1854 and explains re-naming “this spring Ojo de Inez, or Inez’s Spring, after her. I believe it is known to the Mexicans as Ojo de Galvin or Hawk Spring?” (page 362 this can be removed) The spring remains yet today, titled as Ciénaga Spring, although Ojo de Inez can be found on older maps of the Southwest before statehood.

This drawing illustrates what one scholar described as “an idealization of the difficulties of the march” where the survey party muleteers struggle to save pack mules sinking in quicksand, Bartlett gesturing “with noblesse oblige toward the scene as if he were giving a lecture at the Athenaeum” while Inez remains perched, side-saddle atop a mule, attired in a typical Catholic, lace headscarf, shoulders draped with a quechquémitl and a cotton, ankle-length dress as she sits, mounted side-saddle. Along with hundreds of work from the Commissions two-years labor, this sketch, John Russell Bartlett, Fording a Stream, Packmules Sink in Quicksand, September 13, 1851, 10” x 12 ¾”, Pencil and Sepia wash is preserved at the John Carter Brown Library, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island.

Al O’Brian built this house in the early 1930s with rock harvested from an abandoned calvary building on the ranch. The original structure was constructed with limestone material taken from a quarry on the ranch that also served as a source for a number of Civilian Conservation Core (CCC) structures that remain throughout the area.

The Ray Gunn’s stone and tree-trunk dugout home predates the Al O’Brian house by several years and sits next to Gunn Canyon, one of the three large canyons on the ranch that drain into the Burro Ciénaga. An elderly neighbor lady told us she and her husband once leased and ran cattle on the Pitchfork Ranch and hired Ray Gunn as a day labor during the roundup. He was apparently difficult to work with and their Hispanic ranch manager told her at the day’s end: “Yo trabaho con el pistola no mas.” (I’ll not work with the pistol any more.)

Located on the north portion of the ranch, this old natural artifact illustrates just how different the desertified Southwest is from the habitat the Spanish found when they arrived. There are no longer trees anywhere near this size any on the ranch.

Like most historic cattle operations, this ranch has 6 windmills and steel rims used for storing water. Two have long been out of use, but the others remain operative. Because of the climate crisis, 3 of the remaining 4 have gone dry, 2 recovered and one persists uninterrupted. The climate crisis is noticeable here in a number of ways, here lies debris and sediment gathered over the last century or more on the floor of a dried up steel rim.

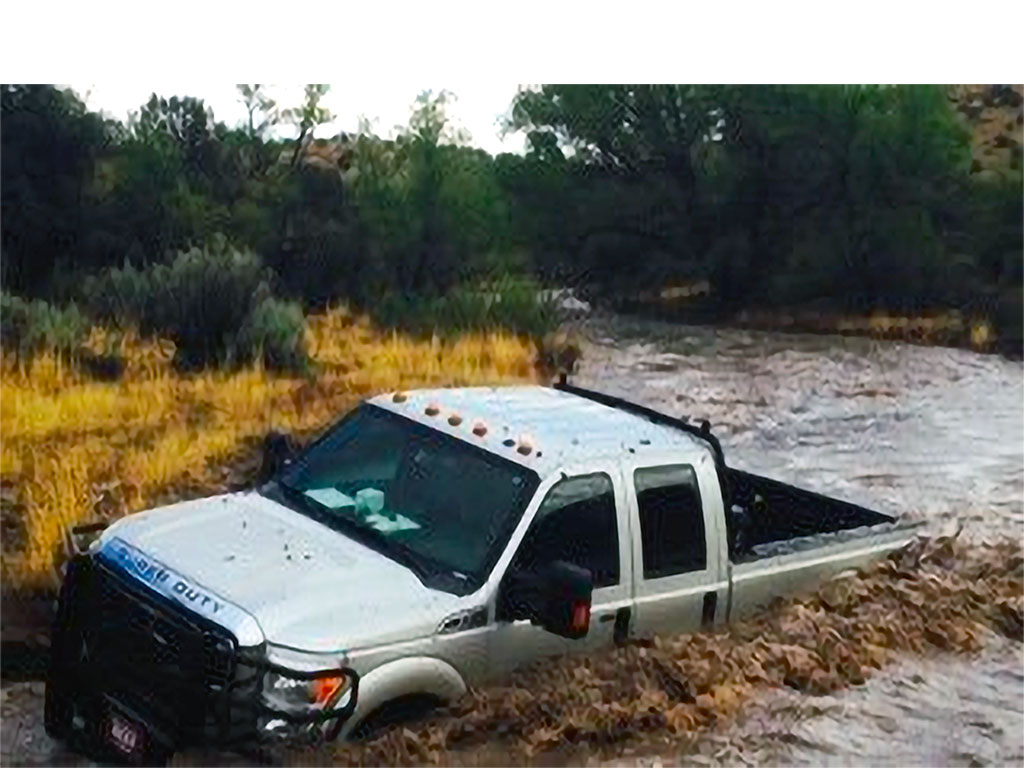

Hazards of Driving on the Ranch

2013

2010

2007

A neighbor stuck on Separ Road, 2014