Ciénagas: Important and Endangered Habitats

Everyone knows what a river is, and even those unconcerned about the environment know the importance of clean, drinkable water. Most people are familiar with lesser watercourses such as creeks, streams and brooks. But in the American Southwest there is a unique kind of waterway few people know of — the ciénaga. So few ciénagas remain healthy, absent awareness of what ciénagas are and their importance, these endangered habitats may soon become extinct.

As explained below, until late 2018, there were only 155 ciénagas known to exist in the Southwest and, of them, only 68 remain functional or restorable, with 56 percent severely damaged or dead.

These percentages obscure the harsh reality that 95 percent of ciénaga habitat has been lost, and those few that remain are damaged and smaller. Nine miles of the 48-mile-long Burro Ciénaga runs through the Pitchfork Ranch, the upper two miles are historic ciénaga, with three miles of historic ciénaga habitat on two ranches north of the Pitchfork: three miles on the Otto Prevost Ranch and three-quarters of a mile on the C-Bar Ranch.

"Ciénaga" is a Spanish term for desert marsh, bog or shallow, slow moving water. At long last, as ciénagas have become seriously studied, thinking about them has evolved, the definition improved and their function better understood. The ciénaga on the Pitchfork Ranch and those in the arid Southwest might be better labeled Aridland Ciénagas:

Aridland Ciénagas are aquifer or spring-fed, alkaline, wet meadows or marshes with shallow-gradient, permanently saturated soils in otherwise arid landscapes that historically supported lush meadow grasses, sedges, rushes, reeds and a variety of endemic species, often occupying the entire width of valley bottoms.

To better understand what ciénagas are, it’s helpful to know what they are not. An Aridland Cienaga is not a swamp-like salt marsh that exists in the Ciénaga de Zapata located on the Zapata Peninsula in the southern Matanzas Province in Cuba. Ciénaga de Zapata has salt-tolerant trees, while healthy Aridland Ciénagas are treeless except where water returns underground near their end or along their borders. Also known as a coastal salt marsh or tidal marsh, these coastal intertidal zones between land and open saltwater are regularly flooded by tides, rather than freshwater or spring-fed, oasis-like habitat that is the Aridland Ciénaga of the desertified Southwest. Aridland Ciénagas are also not high-mountain meadows that occur above 2000 meters or 6,562 feet, rather, Aridland Ciénagas are supported by springs or groundwater seeps, occurring below 6,562 feet elevation.

Because there are substantial geographic variations where arid-land ciénagas are found, there are, in effect, two species of ciénagas in the Southwest, what might be thought of as Karst-Based Aridland Ciénagas and Spring-Sourced Aridland Ciénagas. Most ciénagas in West Texas and adjacent Coahuila (e.g. Cuatro Ciénegas) and those of the Pecos in New Mexico are the product of karst aquifers and their springs. Karst is a special type of landscape that is formed by the dissolution of soluble rocks, including limestone and dolomite. Approximately 20 percent of the land surface in the United States is karst and roughly 20 percent of all groundwater withdrawals came from karst aquifers. The suggestion, not mine, is that this species of ciénaga be called “Karst-Base Aridland Ciénagas.” The sources of these springs are discrete and don't move as they are controlled by deep underlying hard-rock geology. They may have very little or no upstream surface watershed feeding them, and if they do, those watersheds rarely have surface flows. Most karst-based ciénagas receive very little sediment input, fed as they are by deep, sediment-free aquifer discharges, often having negligible upstream surface watersheds. Soils, slope and exposure affect downstream extent, but the upper end of the system never moves. Where springs capable of supporting ciénagas occur in stream channels (which is common), ciénaga-like vegetation may develop and persist for short times, but is inevitably stripped away by floods produced in the upstream watershed. Impacts of water extraction on these may come from far away as upstream contributing aquifers are depleted anywhere between recharge zones and the spring discharges that feed them, impacts that often incur well outside of the surface watershed in which the spring occurs.

Finally, in an effort to promote clarity in the world of ciénagas, it is helpful to recognize a good deal of mixed usage has surrounded the elusive term “ciénaga.” It has eight spellings, three pronunciations and until recently, a hazy definition that is continuing to be refined. The word is a derivative of the Spanish term cieno for silt. When we set up this website, our understanding was that the word was commonly attributed to "cien-aguas" or literally "100-waters.” “You hear, too, of chenegays (one or more springs together; a corruption of the Spanish cien aguas—hundred fountains).” Two Thousand Miles on Horseback, Santa Fe and Back, A Summer Through Kansas, Nebraska, Colorado, and New Mexico, in the Year 1866, James F. Meline, Horn & Wallace Publishers, Albuquerque, New Mexico, 1966, 58. This rather vague or fuzzy term is more commonly spelled in the Southwest with a second e, rather than an a, ciénega. The name for the Burro Ciénaga that courses through this ranch uses the a spelling and is found that way on historic maps. The spelling with an a arguably reflected the a in aquas, so the “100-waters,” and a spelling made sense to us. Although 100-waters may have merit in terms of colloquial origin, The Real Academia Española is clear that the word is not related to either 100 or water, rather is derivative of the Latin term for silt (Del lat. *caen ca, de caenum) or cieno in Spanish. The dictionary lists “ciénaga” as derived from “ciénega.” With the root of “cieno” or “silt,” there is a consistency with the dark, fine, almost charcoal-like soil found in the ciénaga here.

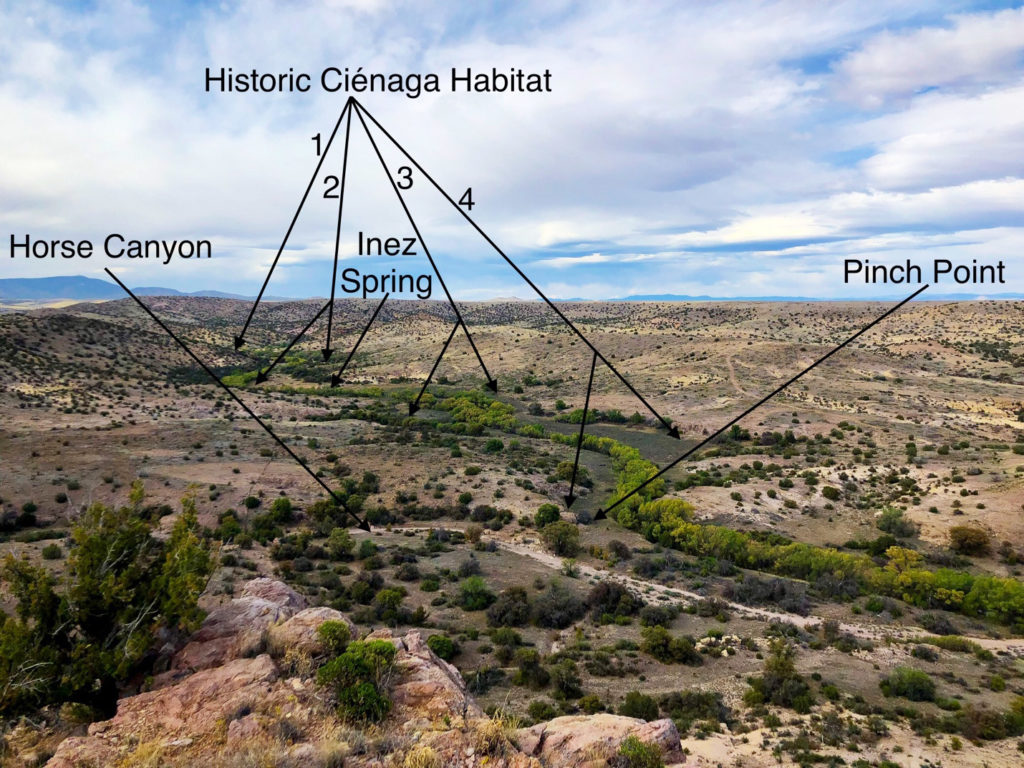

As you can see on the Burro Ciénaga Watershed and Surrounds map in The Ranch section on the navigation bar, the Burro Ciénaga watercourse is in the midst of a 56-square mile watershed and runs a total of 48-miles down to and then under I-10 and turns eastward towards Lordsburg where it empties into a playa. Only the upper 5-miles of the water way was authentic ciénaga habitat, the 43-mile balance is riverine riparian. A thousand years ago, this “river” (it was a river then, but is no longer) flowed full time because there is a 5.6-acre Mimbres site on the lower portion of the Pitchfork that Archaeologist Patricia A. Gilman, University of Oklahoma that was inhabited continuously from 750 BP to 1130 BP. This photograph and diagram by Nathan McIntyre illustrate the ciénaga portion of the watercourse that remains wet, functioning much like a creek, a mere shadow of its former self. With restoration, this will eventually become a fully functioning ciénaga. Healthy ciénagas don’t have trees because they can’t sprout or persist in permanent water. This incised ciénaga has hundreds of Gooding’s willow trees on both sides of the incised channel that will eventually drown as restoration is completed.

As you can see on the Burro Ciénaga Watershed and Surrounds map in The Ranch section on the navigation bar, the Burro Ciénaga watercourse is in the midst of a 56-square mile watershed and runs a total of 48-miles down to and then under I-10 and turns eastward towards Lordsburg where it empties into a playa. Only the upper 5-miles of the water way was authentic ciénaga habitat, the 43-mile balance is riverine riparian. A thousand years ago, this “river” (it was a river then, but is no longer) flowed full time because there is a 5.6-acre Mimbres site on the lower portion of the Pitchfork that Archaeologist Patricia A. Gilman, University of Oklahoma that was inhabited continuously from 750 BP to 1130 BP. This photograph and diagram by Nathan McIntyre illustrate the ciénaga portion of the watercourse that remains wet, functioning much like a creek, a mere shadow of its former self. With restoration, this will eventually become a fully functioning ciénaga. Healthy ciénagas don’t have trees because they can’t sprout or persist in permanent water. This incised ciénaga has hundreds of Gooding’s willow trees on both sides of the incised channel that will eventually drown as restoration is completed.

The four numbered arrows direct you to the three ranches that contain the 5-mile reach of the ciénaga. Arrow #1 points beyond the mountain ridge to the unobservable 2,670 acres that remain of the historic Otto Prevost Ranch where White Tail, C-Bar and Walking X Canyons converge to form the headwaters of the Burro Ciénaga. It then courses 3-miles south onto #2, the C-Bar Ranch, for about half a mile. Inez Spring is on the Pitchfork Ranch near the border of the C-Bar Ranch where the ciénaga continues for about another 1.5-miles on the Pitchfork and eventually ends at the Pinch Point or possibly below that arrow another quarter mile where Horse Canyon drains into the Burro Ciénaga. The width of the historic, non-damaged ciénega went from the toe of the mountains where arrows #s 2, 3 and 4 point, across to the toe of the mountain on the opposite side, as indicated by the three-branched arrows #2, #3 and #4. Settlers built “dikes, ditches and dams” to keep flood flows from accessing their new, formally ciénaga, richly soiled agricultural fields. Recontouring was arguably the worst cause of de-watering this ciénaga, along with Spanish over-stalking of sheep and elimination of fire, the eradication of bever, drought, over-stalking of cattle and now the climate crisis.

The six images below are photographs of the historic ciénaga habitat in the upper 1.5-mile portion of the 9-mile reach on the ranch of the 48-mile long Burro Ciénaga watercourse.

The first three photographs below are examples of undamaged or un-incised ciénagas. They require only preservation and little or no restoration. The fourth photograph is of the San Simon Ciénega on the Arizona/New Mexico border that is completely dewatered because of groundwater pumping for pecans in Arizona. It is un-restorable and an example of what the ciénaga on the Pitchfork Ranch and Otto Prevost Ranch north of us would have eventually looked like had the erosion causing the incision been allowed to persist. Installation of grade-control structures has arrested the erosion that led to the down-cutting causing the waterway to incise deeper and reversed to process so the ciénaga here is now aggrading, as much as four feet in some areas and at least a foot or more throughout the balance of the portion of the Burro Ciénaga on the ranch.

Thomas A. Minckley (2008)

The Cloverdale Ciénega in the Bootheel region of southwest New Mexico is typical of what an undamaged ciénaga looks like and how the many hundreds, if not thousands, of ciénagas functioned before European arrival.

In December 2018, Robert Sivinski conducted a study for the New Mexico Environmental Department Surface Water Quality Bureau searching New Mexico for previously unstudied or unrecognized ciénagas and located 100 “new” ciénagas in the state: “Wetlands Action Plan, Arid-Land Spring Ciénegas of New Mexico. Although these discoveries are small, remnant shadows of their former selves, this is an important step towards increasing recognition of these critical desert waters. See env.nm.gov > ClearingTheWaters_Fall-2019-online

See also Christina M. Selby’s “Las Ciénegas: The American Southwest’s Most Endangered Ecosystems,” Savingbeautyfilm.com and Wikipedia: Ciénagas.

As discoveries are made and further studies pursued, before European arrival ciénaga numbers were likely in the thousands, but quickly disappeared as new uses of the landscape desertified the Southwest and rendered ciénagas nearly extinct. Another water feature that is extinct, is the sumidero, a 10 to 20 feet wide, deep mud springs feature whose surface mud baked dry. The dangerous sumidero was indistinguishable from the safe surrounding ground, causing the disappearance of horseman, cow or wildlife. Adolph Bandelier wrote that these hidden springs as “hidden springs, with nothing to indicate their presence on the surface. They are pits, constantly filled with mud beneath a thin upper crust. Anyone dropping into them must die unless help is on the spot.” Marc Simmons, “Trail Dust: Men, Animals Disappeared into Pits Called ‘Sumideros,’” Trail Dust, Posted: Friday, June 21, 2013 8:45pm, Updated: 8:44 pm, Sat. June 22, 2013.