Aquatic Macroinvertebrates

Despite 17-years of work restoring the ciénaga and uplands on this ranch, we failed to give aquatic macroinvertebrates their due, but we’ve finally paid attention to these remarkable animals. “Aquatic” means water, “macro” indicates big (at least large enough to be seen without a microscope), and “invertebrate” denotes the absence of a backbone. These spineless water bugs can be seen with the naked eye.

There are aquatic macroinvertebrates that spend their entire lives in water, while many live in the water only when they are very young. As these bugs reach maturity, larvae metamorphose and leave the water, spending their adult life on land. These insects are often adults for a very short time. Mayflies live in streams for months or even years but survive on land for only a few days. During their terrestrial period, they mate and lay their eggs in or near water where their life cycle continues.

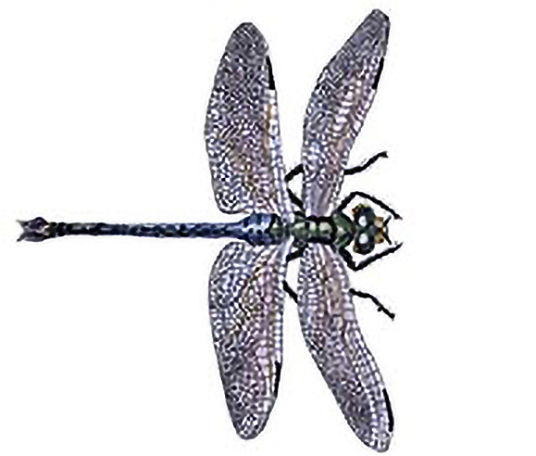

The larvae and adult forms of aquatic macroinvertebrates don’t look alike, although they are similar in many ways – the dragonfly larvae and adult dragonfly shown below are both skilled predators.

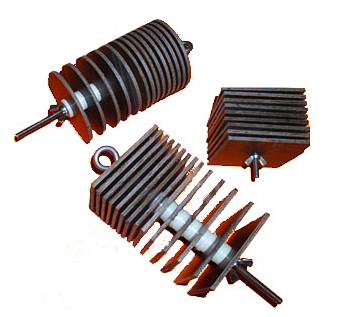

In late 2019 I attended a Wetlands Round Table in Las Cruces, New Mexico where Wiebke J. Boeing, Professor in Aquatic Ecology, Department of Fish, Wildlife and Conservation Ecology at New Mexico State University in Los Cruces, New Mexico made a presentation. We reached out to her, she visited the ranch and decided to sample the ciénaga for benthic – (benthic refers to anything associated with or occurring on the bottom of a body of water) invertebrates using Hester-Dendy plate samplers (H-D plates). Cinda and I installed the H-D plates at three locations, Wiebke retrieved them several months later and she had a student, Mariangel Varela, process the samples.

Because Wiebke, her students and the rest of the world are in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, Wiebke is teaching virtually and making a variety of adjustments to continue with the necessities of instruction. One of many changes was to have Mariangel take the H-D plates home and process them makeshift. She started in her bathtub, “angel-rigged” a microscope and photographed the specimens with her iPhone. As is apparent from the pictures below, Angel handled the task well.

Wiebke was surprised at how few specimens were recovered, that the diversity overall was low and speculated that the severity of the long-established damage to the ciénaga and recent restoration efforts might provide an explanation for the paucity of macroinvertebrates. Our thinking is that the century-long damage and now the recent habitat changes and improvements mean that it might take more time for new species to establish themselves. We also wonder if it’s possible the presence of the Gila topminnow, Chiricahua leopard frogs, snakes and birds are hampering their efforts to establish suitable refuge that protects them from predation in the recovering, severely incised ciénaga.

Hester-Dendy plates

The aquatic insects that follow are also taken on the ranch, but with a regular camera, either in situ or after capture and placement in a zip-lock sandwich bag.